News

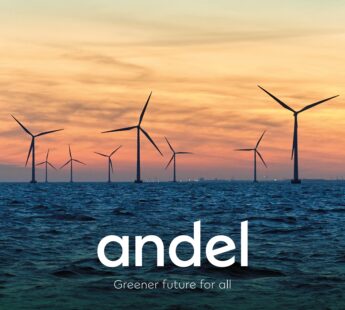

Offshore wind

Wind energy

Wind research and development

+1

Witness the world’s largest wind turbine blade

When Denmark began exporting wind turbines in the 1980s, the blades had a length of approximately seven metres. Since then, researchers and businesses have worked diligently to make the blades longer—because large wind turbines produce more power.

Today, we often see 70-metre wind turbine blades, but there is a limit. In fact, it is rule of thumb that if the length of wind turbine blades is doubled, the wind turbine produces four times as much power. However, the blades become eight times as heavy.

In collaboration with researchers from DTU Wind Energy, LM Wind Power—one of the world’s leading wind turbine blade producers—decided to solve this scaling problem.

And the result? That three mega blades—each with a length of 88.4 metres—are right now rotating and producing power on a test wind turbine in Germany.

-Related news: One-Of-A-Kind Wind Tunnel Inaugurated

The market is demanding large blades

LM Wind Power, Aalborg University, and DTU started the joint mega blade project in 2008 with funding from the Danish National Advanced Technology Foundation (now Innovation Fund Denmark). The original object of ‘Blade King’—as the project was called—was to make mass production of wind turbines easier, to saturate a market that was hungry for wind technology.

But with the onset of the financial crisis, there was a global decline in the demand for wind technology, and the objective of the collaboration was changed. Instead of producing many blades quickly, the focus was switched to the development of few, but larger, blades, which were to be competitive in the long term.

“Today, more customers are demanding larger offshore wind turbines than previously. They produce more power than small onshore wind turbines can produce, and therefore they will be more competitive on a market with a constant decline in electricity prices. So we made the right decision,” says Senior Project Manager at LM Wind Power, Klavs Jespersen.

-Related news: Vestas Tests Wind and Solar Hybrid Demonstrator

Since the turn of the millennium, the number of Danish onshore wind turbines has decreased by just over 10 per cent from 6,193 to 5,587, according to the latest figures from the Danish Energy Agency. In the same period, the number of larger and more powerful offshore wind turbines has increased from 41 to 509. An increase of more than 1,000 per cent.

“We’ve positioned ourselves as a technological leader in the design of giant wind turbine blades, and we expect to capture a large chunk of the future energy market. The prestige that comes with this title is also important to our revenues when customers are looking for a supplier of large blades,” says Klavs Jespersen.

There are many indications that customers will demand bigger blades in order to offer competitive electricity prices. In fact, in 2017, the 500 Danish offshore wind turbines generated more than half the volume of power produced by the 5,587 onshore wind turbines.

Researchers want to understand the blade

The changed focus for the ‘Blade King’ project meant that the researchers also had to change their focus. From developing a material which was ideal for mass production of steel fibres and thermoplastic, they now had to develop a material for a new purpose.

“You need more rigidity when building bigger blades. So we had to develop a material that was both sufficiently rigid to enable the blades to bear their own weight and light enough for the wind turbine tower to carry them,” says Senior Development Engineer Tom Løgstrup Andersen, DTU Wind Energy.

The solution was a mixture of carbon and glass fibres. Carbon fibres have very high rigidity and low density—making them light in weight. But they are also very expensive and not very strong. In turn, glass fibres have higher density and are therefore heavier than carbon fibres. They are also stronger and have a markedly lower price. By mixing carbon and glass fibres to form a hybrid material in a highly specific—and patented—way, the researchers succeeded in developing a new, innovative, and competitive material.

“What’s interesting is that it’s normally never profitable to use carbon fibre, because it’s too expensive. But because our hybrid material is lighter than the standard material, it also puts less pressure on the entire wind turbine construction, and it reduces installation and transport costs,” says Tom Løgstrup Andersen.

Will they get bigger?

LM Wind Power is satisfied with the result of the joint project:

“With a blade of 88.4 metres, we’ve proved that we’re again a technological platform leader. And it’s perfectly possible to envisage this blade on a second model in the future. It’s also possible that we’ll produce blades which are even bigger, seeing that we now have the material for it. Finally, we have used the same material for the world’s longest onshore blade of 69.3 metres, which is today manufactured in batch production,” says Klavs Jespersen.

Tom Løgstrup Andersen also sees a potential in using the new hybrid material for even bigger blades than those of 88.4 metres. But he points out that bigger blades also pose more challenges in connection with transport, weight, and installation of the wind turbine. LM Wind Power is also familiar with these challenges. In fact, it took nine months simply to plan the transport of the 88.4-metre long blade from the production facilities in Lunderskov outside Kolding to the test centre in Aalborg.

-Source: DTU

You should consider reading

Perspective

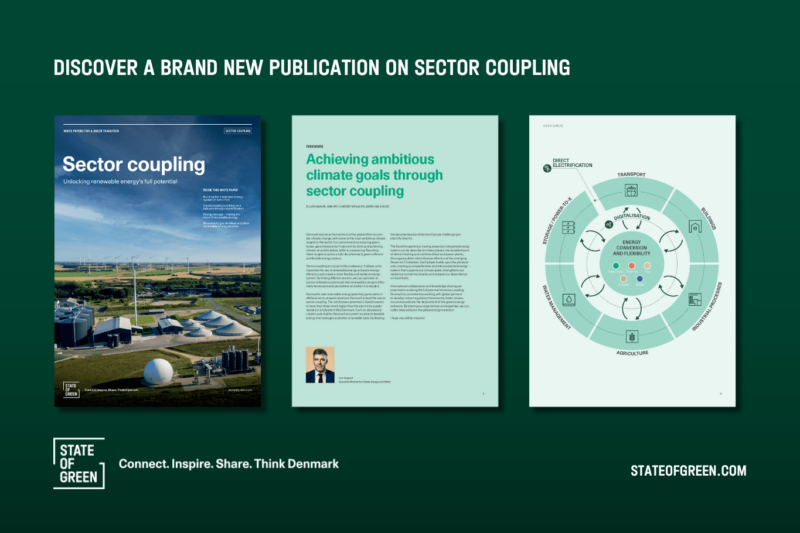

Sector coupling

+9